Asceticism: The Art of Living with Less in a World of More

These ascetic pioneers, such as St. Anthony of Egypt, believed that by stripping away worldly distractions and bodily comforts, they could achieve closer communion with the divine.

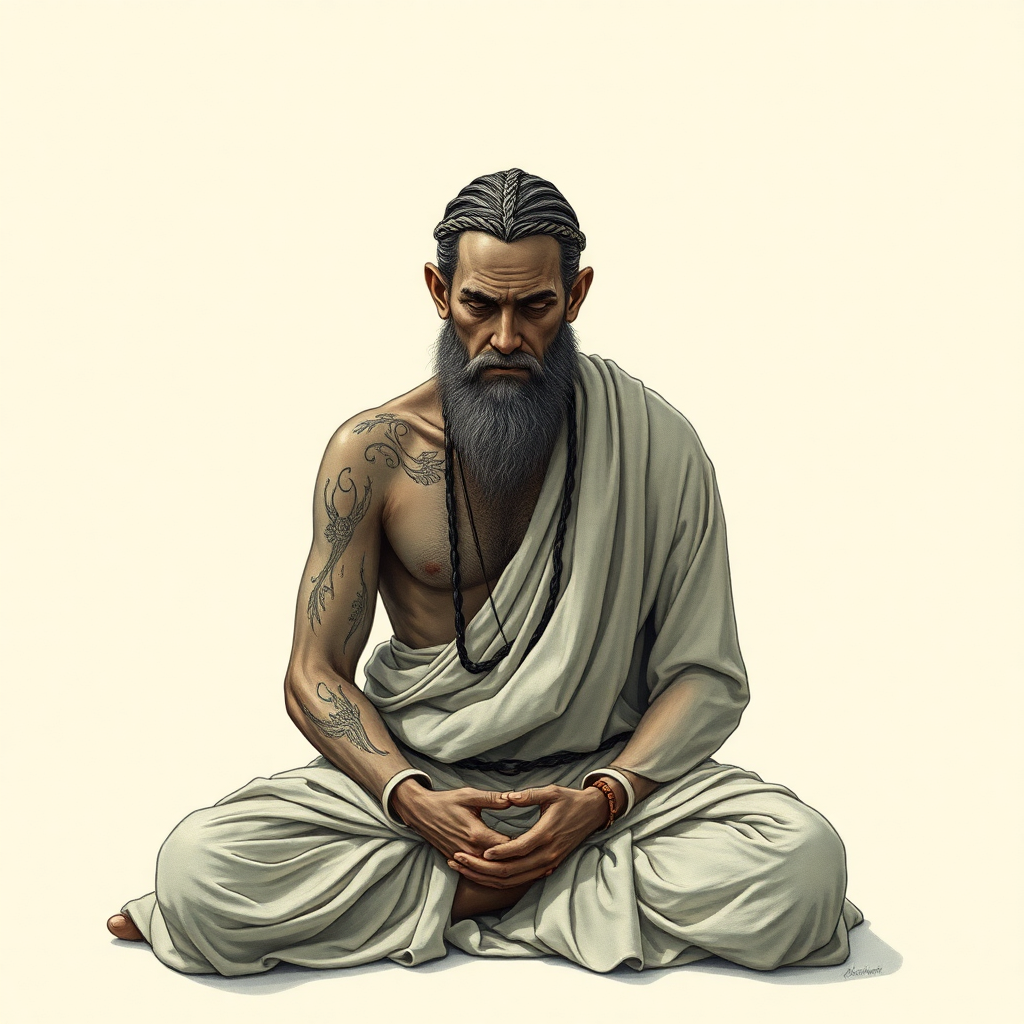

In an age of unprecedented abundance and constant stimulation, the ancient practice of asceticism offers a compelling counternarrative to modern consumer culture. Asceticism, derived from the Greek word "askesis" meaning "exercise" or "training," refers to the deliberate practice of self-discipline and self-denial, often involving the renunciation of worldly pleasures and material possessions in pursuit of spiritual, philosophical, or personal goals. While often associated with religious traditions, asceticism manifests across cultures and contexts as a profound exploration of what it means to live deliberately and purposefully.

The Historical Roots of Ascetic Practice

Asceticism has appeared independently across virtually every major civilization and religious tradition throughout history. Ancient Greek philosophers like Diogenes the Cynic lived in deliberate poverty, sleeping in a barrel and owning nothing but a cloak and walking stick, believing that material possessions corrupted the soul and distracted from philosophical truth. Similarly, the Buddha's renunciation of his princely life to seek enlightenment through meditation and simple living became the foundation for centuries of Buddhist monastic practice.

In the early Christian tradition, desert fathers and mothers retreated to the Egyptian wilderness to live lives of extreme simplicity, prayer, and contemplation. These ascetic pioneers, such as St. Anthony of Egypt, believed that by stripping away worldly distractions and bodily comforts, they could achieve closer communion with the divine. Their practices included fasting, celibacy, poverty, and hours of solitary prayer, establishing patterns that would influence Christian monasticism for millennia.

Hindu traditions developed perhaps the most elaborate philosophical framework for ascetic practice through the concept of the four life stages, or ashramas. The final stage, sannyasa, involves complete renunciation of worldly ties and possessions in pursuit of moksha, or liberation from the cycle of rebirth. This systematic approach to asceticism recognizes that different forms of renunciation may be appropriate at different life stages, offering a more nuanced view than the all-or-nothing approach often associated with ascetic practice.

The Psychology and Philosophy Behind Renunciation

Modern psychology has begun to validate many of the insights that ascetic traditions have maintained for centuries. Research on hedonic adaptation suggests that humans quickly adjust to improved material circumstances, returning to baseline happiness levels despite increased wealth or comfort. This scientific finding echoes the ascetic insight that the pursuit of pleasure and material goods often fails to deliver lasting satisfaction and may even become a source of suffering.

The philosophical underpinnings of asceticism rest on several key insights about human nature and the good life. First is the recognition that desires can become infinite and insatiable if left unchecked, leading to a perpetual state of wanting that prevents contentment. Second is the understanding that external circumstances have limited power to determine inner peace or happiness, which must instead be cultivated through internal practices and attitudes. Third is the belief that voluntary simplicity can paradoxically lead to greater freedom by reducing dependencies and obligations.

Ascetic traditions also emphasize the cultivation of mental discipline and emotional regulation. By practicing voluntary discomfort—through fasting, cold exposure, or sleep deprivation—ascetics develop resilience and discover their capacity to endure difficulties with equanimity. This training builds confidence in one's ability to handle whatever challenges life might present, reducing anxiety about future hardships and increasing appreciation for basic comforts.

Modern Manifestations of Ascetic Principles

While few people today adopt the extreme ascetic practices of ancient monks or hermits, many contemporary movements reflect ascetic principles adapted to modern life. The minimalism movement, popularized by figures like Marie Kondo and Joshua Fields Millburn, encourages people to reduce their possessions to only those items that truly add value to their lives. This practice often leads practitioners to discover that they can be happier with far fewer material goods than they previously believed necessary.

Digital asceticism has emerged as a response to the overwhelming presence of technology and social media in daily life. Digital detoxes, smartphone fasting, and deliberate limitations on screen time represent modern attempts to apply ascetic principles to our relationship with technology. Many practitioners report that reducing their digital consumption leads to increased focus, better sleep, and more meaningful in-person relationships.

The voluntary simplicity movement encompasses a broad range of practices aimed at reducing consumption and focusing on non-material sources of fulfillment. This might include choosing smaller living spaces, growing one's own food, making rather than buying goods, or prioritizing experiences over possessions. Unlike traditional asceticism, voluntary simplicity often emphasizes environmental and social responsibility alongside personal well-being.

The Benefits and Challenges of Ascetic Living

Research and anecdotal evidence suggest that moderate ascetic practices can yield significant psychological and physical benefits. Intermittent fasting, for example, has been shown to improve metabolic health, cognitive function, and longevity while also serving as a form of mental discipline training. Regular meditation practice, which often involves renouncing mental distractions and physical comfort, has demonstrated benefits for stress reduction, emotional regulation, and overall well-being.

However, ascetic practices also carry potential risks and limitations. Extreme asceticism can lead to physical harm, social isolation, and psychological disturbance. The line between beneficial self-discipline and harmful self-denial can be difficult to navigate, particularly for individuals with histories of eating disorders, depression, or other mental health challenges. Additionally, ascetic practices developed in pre-modern contexts may not translate directly to contemporary life without significant adaptation.

The social dimension of asceticism presents particular challenges in modern society. While ancient ascetics often lived in communities of like-minded practitioners, contemporary ascetic practices may conflict with social expectations and professional obligations. The hermit's complete withdrawal from society is neither practical nor desirable for most people today, requiring a more nuanced approach that balances ascetic principles with social engagement and responsibility.

Integrating Ascetic Wisdom into Contemporary Life

The most valuable aspects of ascetic tradition for contemporary life may be found not in extreme practices but in the underlying insights about desire, contentment, and the cultivation of inner resources. Rather than complete renunciation, modern asceticism might involve selective restraint—choosing areas of life where voluntary limitation can enhance rather than diminish overall well-being.

This might mean establishing regular periods of digital silence to cultivate attention and presence, practicing gratitude to counter the constant desire for more, or choosing quality over quantity in relationships, possessions, and experiences. The key insight from ascetic traditions is that freedom often comes not from having more choices but from making deliberate choices about what to embrace and what to release.